What Happens to You if Youve Seen a Grey Alien

The moments that could have accidentally ended humanity

In recent history, a few individuals accept made decisions that could, in theory, accept unleashed killer aliens or set World's atmosphere on burn. What can they tell us nearly attitudes to the existential risks nosotros confront today?

I

In the belatedly 1960s, Nasa faced a conclusion that could have shaped the fate of our species. Following the Apollo eleven Moon landings, the three astronauts were waiting to be picked upwards inside their capsule floating in the Pacific Body of water – and they were hot and uncomfortable. Nasa officials decided to make things more than pleasant for their iii national heroes. The downside? There was a modest possibility of unleashing deadly alien microbes on World.

A couple of decades beforehand, a group of scientists and military officials stood at a similar turning point. As they waited to watch the showtime atomic weapon test, they were enlightened of a potentially catastrophic effect. There was a chance that their experiments might accidentally ignite the temper and destroy all life on the planet.

At a handful of moments in the past century, a few rare groups of people have held the world'south fate in their hands, responsible for the tiny-only-real possibility of causing full catastrophe. Not just the cease of their own lives, but the finish of everything.

And so, what happened that led to these decisions? And what tin they tell u.s. nigh attitudes to the kinds of risks and crises we face up today?

Read more:

- The nuclear mistakes that most acquired World War Three

- Why catastrophes can change the grade of humanity

- Are we living at the 'hinge of history'?

When humanity first made plans to send probes and people into infinite in the mid-20th Century, the issue of contagion came up.

Firstly, there was the fear of "frontwards" contamination – the possibility that World-based life might accidentally hitch a ride into the cosmos. Spacecraft needed to exist sterilised and advisedly packaged before launch. If microbes snuck onboard, it would misfile whatsoever attempts to detect conflicting life. And if there were extra-terrestrial organisms out at that place, we might terminate upward inadvertently killing them with Earth-based leaner or viruses, like the fate of the aliens at the terminate of War of the Worlds. These concerns matter just as much today as they did dorsum in the Space Race era.

A crane lifts the Apollo 11 sheathing onto the ship, just the astronauts were already onboard (Credit: Getty Images)

A second concern was "back" contamination. This was the thought that astronauts, rockets or probes returning to World might bring back life that could show catastrophic, either by outcompeting Earth organisms or something far worse, like consuming all our oxygen.

Back contamination was a fright that Nasa needed to have seriously during the planning of the Apollo missions to the Moon. What if the astronauts brought back something dangerous? At the time, the probability was not considered high – few thought that the Moon was likely to harbour life – but still, the scenario had to be explored, because the consequences were so severe. "Perchance it's sure to 99% that Apollo 11 volition not bring back lunar organisms," said one influential scientist at the time, "but fifty-fifty that 1% of dubiety is likewise big to be complacent about."

Nasa put several quarantine measures in identify – in some cases, a little reluctantly. Concerned officials from the United states of america Public Wellness Service argued for stricter measures than initially planned, twisting the space agency's arm by pointing out that they had the power to refuse border entry to contaminated astronauts. After congressional hearings, Nasa agreed to install a costly quarantine facility on the ship that would pick upwardly the men from their splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. Information technology was too agreed that the lunar explorers would so spend three weeks in isolation before they could hug their families or shake the hand of the president.

However, in that location was a major gap in the quarantine procedure, co-ordinate to the law scholar Jonathan Wiener of Duke University, who writes nigh the episode in a paper most misperceptions of catastrophic hazard.

When the astronauts splashed downwardly, the original protocol stated that they should stay inside the spacecraft. But Nasa had second thoughts after concerns were raised about the astronauts' wellbeing while waiting inside the hot, stuffy space, buffeted by waves. Officials decided instead to open the door, and retrieve the men by raft and helicopter (come across movie at the height of this article). While they wore biocontamination suits and entered the quarantine facility on the ship, equally soon as the sheathing was opened at body of water, the air inside flooded out.

Fortunately, the Apollo 11 mission brought no deadly alien life dorsum to Earth. Just if information technology had, that conclusion to prioritise the brusk-term comfort of the men could accept released it into the body of water during that brief window.

Nuclear anything

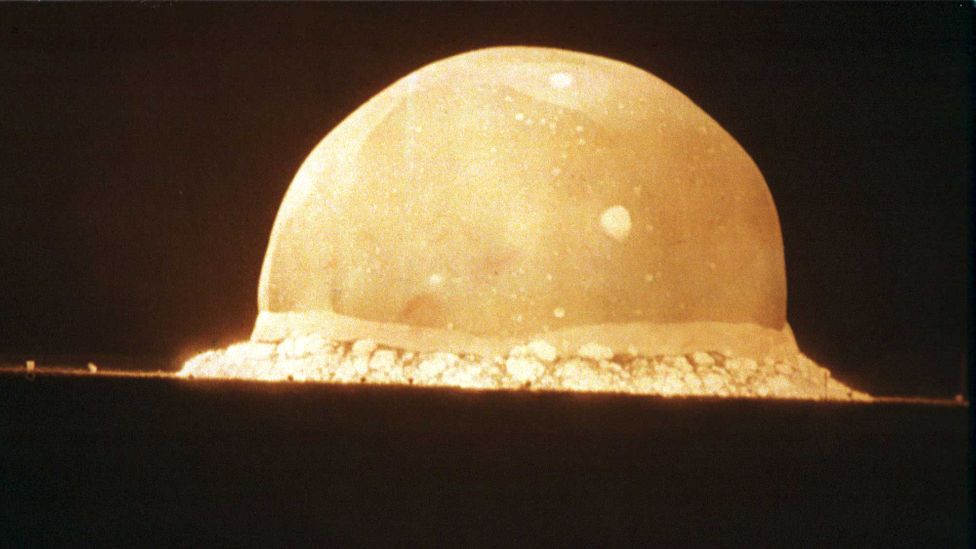

Twenty-iv years earlier, scientists and officials within the The states authorities stood at another turning indicate that involved a small-merely-potentially-disastrous risk. Before the showtime atomic weapons test in 1945, scientists at the Manhattan Project performed calculations that pointed to a chilling possibility. In one scenario they plotted out, the rut from the fission explosion would be so not bad that information technology could trigger runaway fusion. In other words, the examination might accidentally set the atmosphere on fire and burn abroad the oceans, destroying most of the life on Earth.

Subsequent studies suggested that it was nearly likely impossible, but right up until the day of the test, the scientists checked and re-checked their analysis. The day of the Trinity test finally came, and officials decided to go ahead.

The first diminutive weapon exam marked the beginning of a new precipitous era (Credit: Getty Images)

When the wink was longer and brighter than expected, at to the lowest degree one member of the team watching it thought that the worst had happened. One of those was the president of Harvard University whose initial awe rapidly turned to fearfulness. "Not but did [he] have no confidence the bomb would work, but when it did he believed they had botched it with disastrous consequences, and that he was witnessing, every bit he put it, 'the end of the world'," his granddaughter Jennet Conant told the Washington Mail service after writing a book profiling the scientists of the project.

For the philosopher Toby Ord at Oxford University, that moment was a meaning bespeak in human history. He dates the specific time and date of the Trinity test – 05:29 on xvi July 1945 – as the beginning of a new era for humanity, marked by a step-change in our abilities to destroy ourselves. "Suddenly we were unleashing so much energy that we were creating temperatures unprecedented in Earth's unabridged history," Ord writes in his book The Precipice. Despite the rigour of the Manhattan scientists, the calculations were never subjected to the peer review of a disinterested party, he points out, and in that location likewise was no evidence that whatever elected representative was told about the take chances, let lone any other governments. The scientists and military leaders went alee on their own.

Ord also highlights that, in 1954, the scientists got a calculation staggeringly wrong in another nuclear test: instead of an expected half-dozen megatonne explosion, they got 15. "Of the two major thermonuclear calculations fabricated that summer… they got i right and i wrong. It would be a mistake to conclude from this that the subjective risk of igniting the atmosphere was as high equally 50%. Just it was certainly not a level of reliability on which to risk our futurity."

A vulnerable world

From our aware position in the 21st Century, it would exist piece of cake to judge these decisions as specific to their fourth dimension. Scientific knowledge about contamination and life in the Solar System is then much more advanced, and the war between the Allies and the Nazis is long past. Nowadays, no-one would take risks like that again, right?

Sadly not. Whether past accident or otherwise, the possibility of catastrophe is, if anything, greater now than it was back and so.

The Apollo eleven astronauts were quarantined after landing, but at that place was a gap when they were picked upwards at ocean (Credit: Getty Images)

Admittedly, conflicting anything is not the biggest adventure the world faces. Withal, while there may be "planetary protection" policies and labs to guard against alien back contamination, it's an open question how well these regulations and procedures will apply to private ventures that visit other planets and moons in the Solar System. (Adding to the alien catastrophe threat, broadcasting our presence into the galaxy may take chances a potentially disastrous meeting with aliens, especially if they were more avant-garde. History suggests that bad things tend to happen to populations that come across more technologically practiced cultures – look at the fate of indigenous people meeting European settlers.)

More than concerning is the threat of nuclear weapons. A burning atmosphere may be impossible, but a nuclear winter alike to the climatic change that helped to kill off the dinosaurs is non. In WWII, atomic arsenals were non abundant or powerful enough to trigger this disaster, but now they are.

Ord estimates that the gamble of human being extinction in the 20th Century was around one in 100. But he believes it's college now. On top of the natural existential risks that were always there, the potential for a man-made demise has ramped up significantly over the past few decades, he argues. As well every bit the nuclear threat, the prospect of misaligned artificial intelligence has emerged, carbon emissions have skyrocketed, and we can now meddle with the biology of viruses to make them far more deadly.

We're also rendered more vulnerable by global connectivity, misinformation and political intransigence, as the Covid-xix pandemic has shown. "Given everything I know, I put the chance this century at around i in 6 – Russian roulette", he writes. "If nosotros practice not get our human activity together, if we go along to permit our growth in power outstrip that of wisdom, we should expect this take chances to be even college side by side century, and each successive century.

Another way that existential risk researchers have characterised this burgeoning danger is by asking you to imagine picking assurance out of a giant urn. Each ball represents a new engineering science, discovery, or invention. The vast majority of them are white, or grayness. A white ball represents a skillful advance for humanity, like the discovery of lather. A grey ball represents a mixed blessing, like social media. Inside the urn, yet, there are a handful of blackness assurance. They are exceedingly rare, merely pick ane out, and y'all accept destroyed humanity.

This is called the "vulnerable world hypothesis", and highlights the trouble of preparing for very rare, very unsafe events in our hereafter. So far, we haven't picked out a black ball, only that's most probable to be because they are so uncommon – and our hand has already brushed against one or two equally we reached into the urn. In brusk, we've been lucky.

There are many technologies or discoveries that could turn out to exist black balls. Some we know about already, but haven't implemented, such as nuclear weapons or bioengineered viruses. Others are known unknowns, such as automobile learning or genomic applied science. Others are unknown unknowns: nosotros don't even know they are dangerous, because they haven't been conceived of yet.

The tragedy of the uncommons

Why practise we fail to care for these catastrophic risks with the gravity they deserve? Wiener has some suggestions. He describes the way that people misperceive extreme catastrophic risks as "tragedies of the uncommons".

Yous accept probably heard of the tragedy of the commons: it describes the way that self-interested individuals mismanage a communal resource. Each person does what'southward best for themself, only everybody ends up suffering. It underlies climate change, deforestation or overfishing.

The site of the Trinity examination today, beneath an temper that was fortunately non fix alight (Credit: Getty Images)

A tragedy of the uncommons is dissimilar, explains Wiener. Rather than people mismanaging a shared resource, here people are misperceiving a rare catastrophic chance.

He proposes three reasons why this happens:

The first is the "unavailability" of rare catastrophes. Recent, salient events are easier to bring to listen than events that have never happened. The encephalon tends to construct the future with a collage of memories well-nigh the past. If a risk leads the news – terrorism, for case – public concern grows, politicians deed, tech gets invented, and so on. The special difficulty of foreseeing tragedies of the uncommons, even so, is that it is impossible to learn from experience. They never appear in headlines. But one time they happen, that's it, game over.

The second reason nosotros misperceive very rare catastrophies is the "numbing" upshot of a massive disaster. Psychologists find that people's business does not grow linearly with the severity of a catastrophe. Or to put it more bluntly, if you inquire people how much they care nearly all people on Earth dying, it's not vii-and-half billion times more than business organization than if y'all told them one person would die. Nor practise they account for the lives of hereafter generations lost either. At large numbers, at that place's some prove that people's business even drops relative to their concerns about individual tragedy. In a recent article for BBC Future about the psychology of numbing, the journalist Tiffanie Wen quotes Mother Teresa, who said: "If I look at the mass I will never deed. If I look at the 1, I will."

Finally, Wiener describes an "underdeterrence" effect that encourages a laissez-faire attitude among those taking the risks, considering there is no accountability. If the world ends because of your decisions, so y'all can't become sued for negligence. Laws and rules have no power to deter species-ending recklessness.

Perhaps the most troubling thing is that a tragedy of the uncommons could happen by blow – whether it'due south via hubris, stupidity, or neglect.

"All else being equal, not many people would prefer to destroy the world. Even faceless corporations, meddling governments, reckless scientists, and other agents of doom require a world in which to accomplish their goals of profit, order, tenure, or other villainies," the AI researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky one time wrote. "If our extinction proceeds slowly plenty to allow a moment of horrified realisation, the doers of the human activity volition likely exist quite taken ashamed… if the World is destroyed, it will probably be by mistake."

Nosotros tin can be thankful that the Apollo 11 officials and Manhattan scientists were not those horrified individuals. Merely anytime in the time to come, someone will go far at some other turning signal where the fate of the species is theirs to determine. Or perhaps they are already on that road, hurtling towards disaster with their eyes closed. Hopefully, for the sake of humanity, they will make the right choice when their moment comes.

--

Richard Fisher is a senior announcer for BBC Hereafter. Twitter: @rifish

Bring together 1 million Time to come fans past liking us on Facebook , or follow united states on Twitter or Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Culture ,Worklife, and Travel , delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210217-the-moments-that-we-could-have-destroyed-humanity

0 Response to "What Happens to You if Youve Seen a Grey Alien"

Postar um comentário